The tricky thing about commit messages is they seem unimportant when you are writing them because you know what changes you just made and why you made them and the code is right there so it is obvious. Those are incorrect assumptions.

Commit messages are important because when someone is reviewing your work they set the stage for what the changeset contains, they set the mood for the diff someone is about to read. The code is not always ‘right there’, the git log command does not show patch information by default, nor does the GitHub pull request page, nor the GitHub commits page. In all these cases you can get to the diff for the commit but it is an extra step. If you write good commit messages it is one the reviewer only needs to take for a commit in which they are particularly interested.

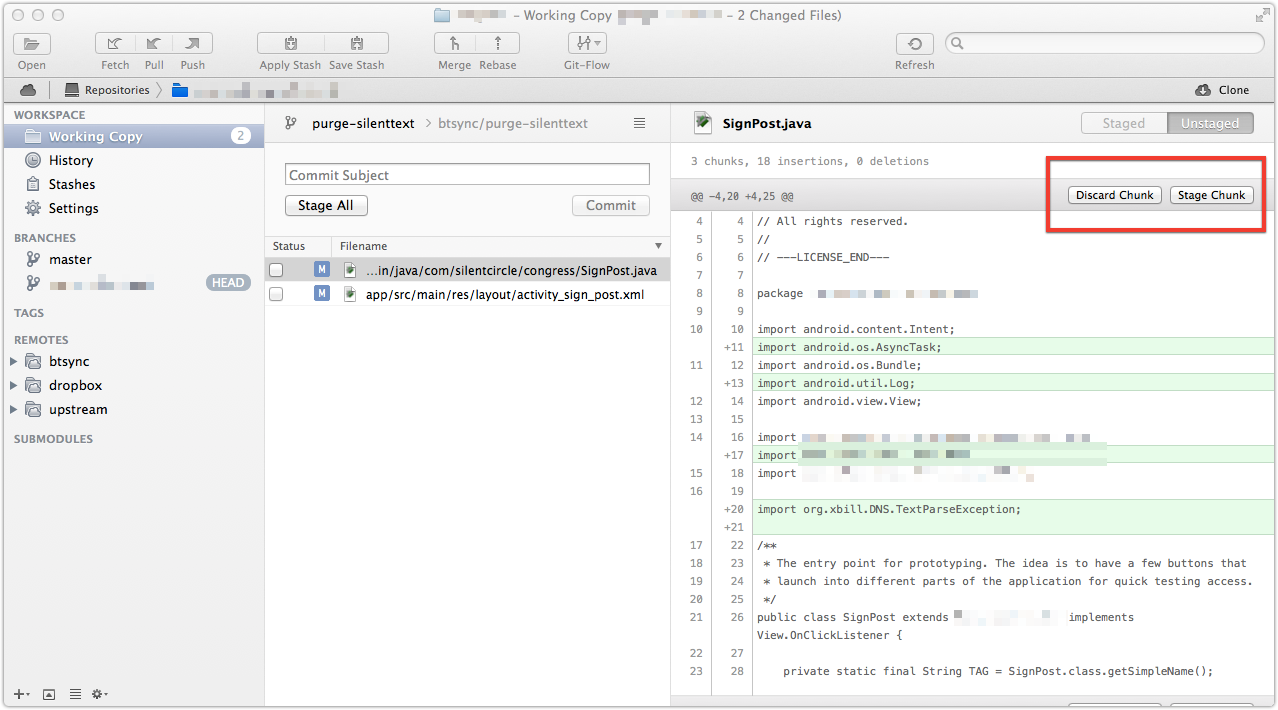

A part of writing good commit messages is creating good commits. It is exceedingly difficult to think in terms of good commits while doing the work, so don’t make the attempt. Start a task from a clean working copy and work on the task until a meaningful change has been made. A meaningful change could be a new screen, it could be a re-factoring, it could be the addition of a feature. A meaningful change is a self-contained unit of work but it is not necessarily a single commit. In order to craft a good commit you will likely need to break up the self-contained unit of work into several commits. The need to break down units of work into commits is why git provides git add --patch and git reset --patch commands. git add --patch steps through all of the changes that show up in git diff and lets you stage them, or not. Tower provides this functionality when you select a changed file (not check the box), it will show you all the changes as ‘hunks’ (git add --patch calls them hunks as well) and let you stage them independently. It is possible to break down hunks even further by editing them to stage stage individual lines (e or edit on the command line, in Tower you do it by selecting the line numbers).

When crafting commits I try to build up to the full functionality by creating commits for the supporting pieces first, my goal is to have every commit compile or run. I don’t test for this, it isn’t important if you are working in feature branches but it does provide a guideline for how much to include in a commit. For example, I’m adding a new screen to an Android application and the new screen in Activity#onCreate calls an API method I’ve created for the Activity. In this overly simplistic case, I would first commit the change that creating the new API method and then commit the change creating the new screen (Activity and associated layout files). That’s one unit of work but at least two commits.

Creating good commits and writing good commit messages is tough to learn because no one teaches it. It is a skill built up over time through experience and the occaisionally heavy handed guidance of team leads. Team leads harp on it because they are the people reading the output of git log and reviewing pull requests to see what has changed, make their lives easier write good commits and messages.